I am not a fan of the unadorned vernacular in poetry, no matter how sincere its sentiment or pertinent its message. In my book, what a poet should do is invent wonderful turns of phrases, new syntax, head-turning semantics. There should be a dialectic of differences which interacts to create the magical, entirely new, entirely necessary synthesis. A poet should bring brilliant LANGUAGE to the reader, by which I more nearly mean semiotics, meaningful, culturally rich, innovative signs that the reader gets to deconstruct time and time again. If you are tired of reading monosyllabic laundry list poetry, then you will be delighted by Marc Vincenz, a poet who trucks in the unpredictable and unexpected, and who conjoins words like gems for jewelry.

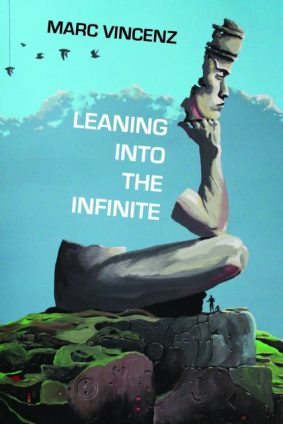

In Leaning into the Infinite, Vincenz displays a magical imagination that mines from three continents and a dozen cultures. The language is literate and sparkling. Look at a typical title: “When Uncle Fernando Conjures Up a Dead-Bird Theory of Everything,” where Fernando is “Portuguese poet, Fernando Pessoa and his many alter egos . . . written under more than seventy heteronyms.” Other inspirations are Li Po, Wang Wei, Kafka, Paracelsus, Heraclitus, and Robert Bly. If Auden multitasked, if cummings studied alchemy, if Borges reincarnated into a Hong Kong-born British-Swiss living in America on a green card, you might get a Marc Vincenz.

Vincenz’s Infinite is a poetry of mind, a garden of images and ideas and characters that is uncannily aware of its reader. Perhaps all good poetry has this in common, this drawing of the reader in, like an accomplice to its art. Vincenz’s poetry engages and questions, implicitly and explicitly: “How?” “Should I?” “Who?” In “Unreliable Narrator,” he asks “Should I be / stumped / by the greatness / of God . . .”

Who then is

the protagonist

when trillions

of single cells

all think

for themselves?—or together?—

The poet asks and the spare Basho–like verses —and rich longlined poems later in the collection—wait for answer. The poet’s elegant use of line breaks and sculpted white space seem to invite readers to reply, to mark Leaning into the Infinite up with all kinds of marginalia.

We have a tradition in the European canon of the philosopher-poet, in which a poet offers insights into the human condition. Modern poets do so ponderously as a whole. Vincenz’s touch on this is so light and his language so original that you scarcely know you are being enlightened. His temporal range is from the nascent prehistory of cave paintings to the post-relativistic twenty-first century. His worlds are populated with extraordinary beings, including the aforementioned Uncle Fernando and his interlocutor, the oracular Sibyl. In “Uncle Fernando & Sibyl Exchange Curt Words,” Fernando asks for “that mythical moment” and the oracle replies, “Hush,”:

Carbon first.

Then light.

Sibyl, Vincenz’s untamed muse, also appears in dialogues between Prometheus and Orpheus:

Orpheus: Prometheus:

The voice & what

of time is that perfume—

… . . .

within the planes the word made

of being Thing

… . . .

Sibyl:

whenever I start

to try & explain it

I forget words

altogether

My favorite characters in Leaning into the Infinite include a finch singing to his mate from a tree-top which he thinks is a mountain, the Tree God Saluwaghnapani, and Milen, a Filipino wet-nurse who sings a song she “claimed drove off demons that grew within Javan / smog clouds: Ai-Li-Ma-Lu-Ma-Nu — . . . “

Leaning into the Infinite ranges from Olympus to “The Penal Colony” and is vivid and visceral:

Not from the gagged mouth—it knots & tangles in the larynx

& the chain simply groans: ‘Have done it.

Have it etched to the bone.’

It’s all in the pointed nib of the writers’ dark truth.

In an enlightened moment the Bewildered gasps alone—

The Orwellian/Kafkaesque boot stamps:

Just Be

a

good Citizen

Be Just

And then the poet escapes to his natal Asia:

O to be born reforested in Borneo

where water doesn’t run off in disappointing sloughs,

but cascades & careens within the bejeweled heart

of a single fruiting tree, where a child is a rambutan

(or the fleshy dumpling-pulp of a mangosteen)— . . .

Vincenz speaks to the childlike longing in us to have a storyteller/mentor introduce us to the world’s mysteries, to share its secrets:

If only I had a good uncle to sit me down at an uneven hearth

with a hot cup of mulled wine, a twinkle in his eye

& this background whiff of ancient pine:

To hear how the world begins green, fresh, tabula rasa:

& late at night or early morning through air still as glass,

to eavesdrop upon the grasses & their endless philosophizing.

You have this uncle in Marc Vincenz. Drink up.

No comments:

Post a Comment